One way that some have avoided the question, "Does God exist?" is to think of our universe as existing in eternity. That is to say, they wish to believe that time had no beginning -- it always existed. They would like to think that time can be traced backward through an innumerable sequence of events.

If this concept is true -- if our universe always existed -- then the argument for the necessity of a Creator is negated. It makes no sense to believe that an omnipotent God created all things "in the beginning" if nothing needed creating, and if there was indeed no beginning.

It is blindly taken for granted by classic, atheistic evolutionists: We came from apes, which came from sea creatures, which came from single-celled organisms, which came from chemical mixtures, which came from the earth, which perhaps came from another celestial body, which was a product of the "Big Bang," which was the result of intensely compressed primordial matter, which, in one form or another, has

always existed! How the "first" physical component came to exist cannot be answered, so it is avoided by assuming its existence in eternity.

How do we deal with this concept?

Here is the answer:

If time has always existed, then I would not now exist. For if I was born at a certain point in time, and if time is a series of sequential events measured from one point to another, then the moment of my birth could never have arrived because there would be no starting point in the time line from which to advance.It's really much simpler than it sounds (at least on the surface level), especially since my ability to express it in precise terms is lacking. Maybe someone can help me with it.

But I think you can understand if you think of it this way:

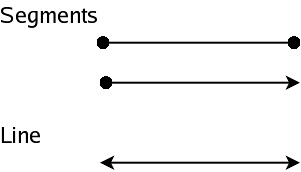

Let's assume that time can be represented by a line. In geometry, a

segment is represented by a point, or a dot, that extends for some distance, but a

line is represented by a segment with arrows on each end, signifying that it extends without interruption in each direction. A

segment, no matter how long, can be measured, but a

line cannot -- it is infinitely long.

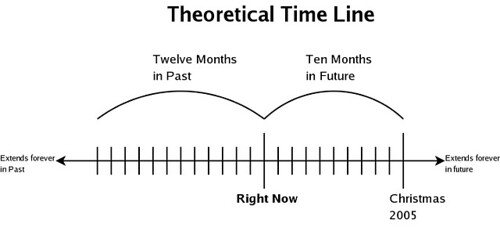

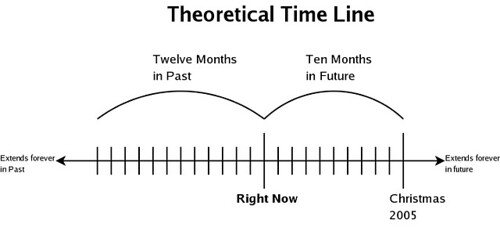

So, assuming time is an infinite line, let's make a mark somewhere on that line to indicate the present time. Then make ten hashmarks to the right, indicating the number of months till Christmas (2005). So now, using the line, you can count the distance from now till Christmas: ten months. What you're looking at is a ten-month

segment of time that has a beginning (February) and an end (December).

Now mark 12 more hashmarks to the left of the present time. The distance between that twelfth mark on the left and the mark representing this Christmas equals one year and ten months. Do it again, and you'll have two years and ten months. Again, three years and ten months. And so on.

You see the pattern. The more marks you make to the left on the time line, the longer it takes to arrive at Christmas 2005.

The left arrow on that time line represents history that cannot be measured; it extends forever into the past. With that understanding, can anyone explain how long the universe will have had to wait until it sees Christmas 2005?

If you had to answer that question today, your answer would have to be: forever plus ten months. But that is mathematically impossible. Is forever really forever if you can add ten months to it? Would that be longer than forever?

So if forever isn't long enough to reach Christmas 2005, then we'll never reach it. If it can't reach that, then it can't reach any "point" in history, including our birthdays, including the founding of our country, including the ice age, including the so-called "Big Bang." That left arrow of "forever past" is invinsible; because of it, you can never

arrive at a certain time, for you are forever in a state of

arriving.

We must therefore conclude that time had a beginning, and that the universe could

not have always existed. It must have come

into existance.

"Well, then, who made God?" the atheist will respond. "You are faced with the very same conundrum."

Our answer is, "That's why we call Him 'God.'" It's a mystery. But while we can't comprehend Him, we can apprehend certain facts about Him.

He has to exist outside the confines of time -- that's the only logical explanation. He therefore never had a first thought, and so is not in the middle of a huge series of thoughts. He is changeless. He is Being. He just plain IS.

That's why this Christmas, ten months from now, should be the "best one ever" -- because it will be the latest occasion to contemplate (and celebrate) the mystery of the timeless God somehow entering time through the Person of Jesus, who is God in the flesh.

The Incarnation -- God becoming man -- is a baffling but beautiful mystery. It cannot be discerned through the sciences or philosophy; it can only be known through divine revelation. At the same time, Jesus is the divine revelation and the Divine Revelator, and He has entrusted His Church to spread the good news of the Kingdom of God until all things are fulfilled.

Now that we are in the season that precedes Easter, we soberly remember that Jesus first came so He could die. He died and was raised from the dead so that we may share in His life, and be complete in Him forever.

Our job now is to "work out our salvation with fear and trembling" (Philippians 2:12), while time is still on our side.